Highlights:

- Mortgage Rates return to 2017 Levels

- Canadian economy falters in first quarter

- Time for the Bank of Canada to cut rates?

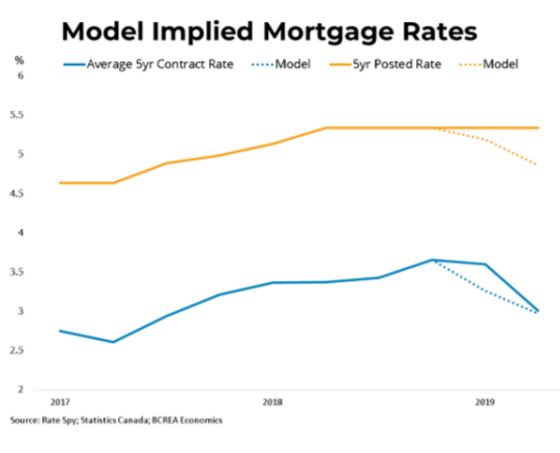

The big news in the Canadian mortgage market is the return of sub 3 percent five-year mortgage rates. The last year of mortgage rate increases has essentially been erased by an acute repricing of bond market expectations. A slowing Canadian economy and rising global trade tensions triggered a sudden change in bond market sentiment late last year, pushing further Bank of Canada rate increases off the table.

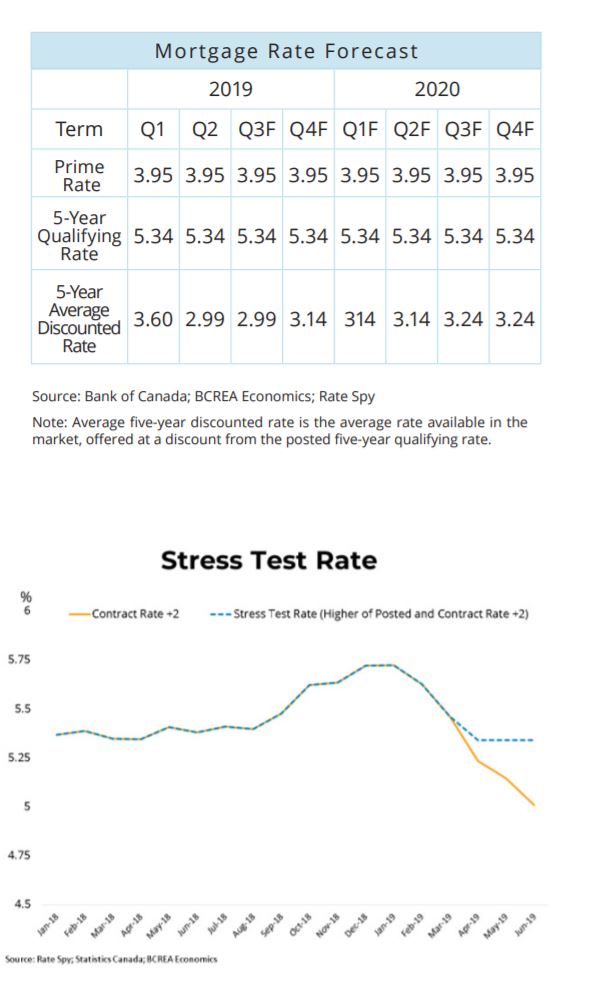

Even though five-year bond yields and five-year contract rates have fallen substantially, the structure of the mortgage stress test allows for limited pass-through to qualifying rates. As currently constituted, the mortgage stress test is the higher of the contract rate plus 2 percent or the posted five-year mortgage rate. The latter has not changed in close to a year despite the drop in five-year bond yields. In fact, the posted rate appears to be divorced from its prior statistical relationship with the five-year bond yield. Our models imply that the five-year posted rate should be 4.84 percent, rather than the current 5.34 percent.

Not only would a lower posted rate help insured buyers to qualify, but it would provide a significant boost to the uninsured market through a lower stress test rate.

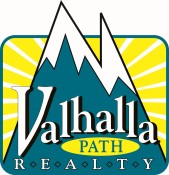

We anticipate that current low mortgage rates will be around for most of the summer before rising modestly into next year. As for the posted rate for insured borrowers, it would be surprising at this point if the posted rate moved at all.

Economic Outlook

Canadian economic growth stagnated through the end of 2018 and the first quarter of 2019, averaging just 0.4 percent growth in real GDP. There were, however, some bright spots in an otherwise feeble first quarter. Canadian consumer spending bounced back, posting the strongest growth in close to two years. Moreover, GDP growth in March came in at a very strong 6 percent annual rate, momentum that should carry over into the second quarter. We are forecasting that the Canadian economy will expand between 1 and 1.5 percent this year, a deceleration from 1.8 percent growth in 2018. That slowdown, along with an uptick in inflation, will likely keep the Bank of Canada sidelined, particularly given the uncertain state of the global economy and the ongoing impact of the B20 stress test on the housing sector.

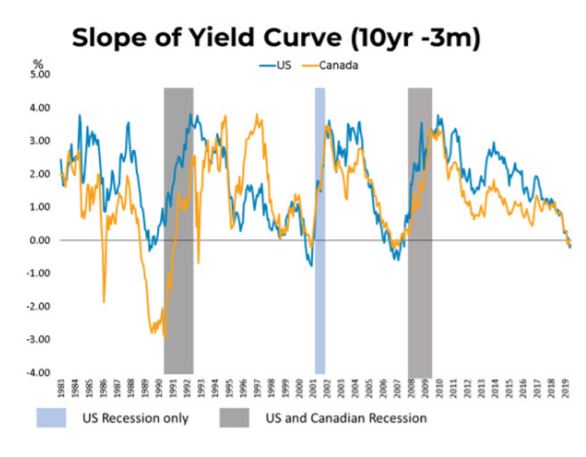

That said, risks to the economy are very clearly tilted to the downside. The US continues to flirt with disaster by engaging in trade wars with China and Mexico. Those actions have the potential to seriously disrupt the global economy and at worst, tip the US into recession. Clearly, financial markets are very concerned about that scenario with both the US and Canadian yield curves inverting. Markets are now expecting both the US and Canadian central banks will begin reversing course on monetary policy and lower rates within a year.

Interest Rate Outlook

With market expectations at odds with communication from the Bank of Canada, it’s worth asking, “Is it time for the Bank of Canada to cut interest rates?”

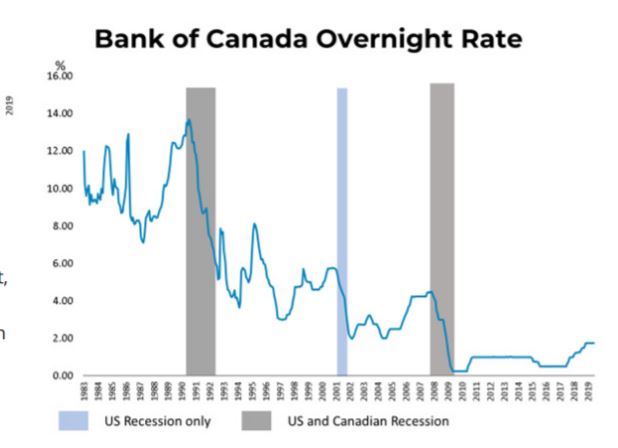

The argument in favour of lower rates is a growing risk of recession, caused by an exogenous shock like the escalation of global trade disputes when the Bank has limited ammunition to boost the economy. During the last Canadian recession, sparked by the 2008 global financial crisis, the Bank of Canada responded by lowering its overnight rate 425 basis. The Bank responded to the 2001 tech bubble and 9/11 attacks by lowering rates by 375 basis points. At an overnight rate of just 1.75 percent, the Bank has a fraction of the usual response at its disposal without venturing into the untested (Canadian) waters of unconventional policy like negative interest rates or quantitative easing. Given that monetary policy acts with long lags, cutting rates today would act as an insurance policy against rising risk of recession in the next year, similar to how the Bank responded to the oil price shock of 2015.

Conversely, the Bank and the Federal government are both set on finally bending the household debt-to-income curve and are hesitant to ignite a borrowing binge by Canadian households. Moreover, inflation is slightly above its 2 percent target and the Canadian unemployment rate is sitting at a record low. Hardly the usual conditions for a looser monetary policy.

Copyright BCREA – reprinted with permission